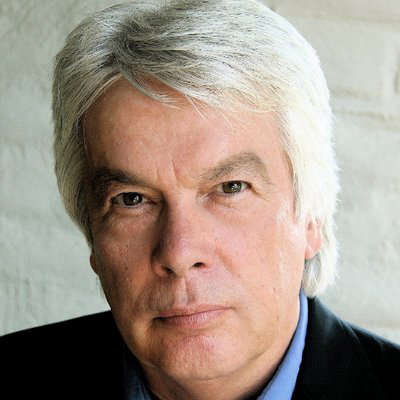

By Alan Minsky

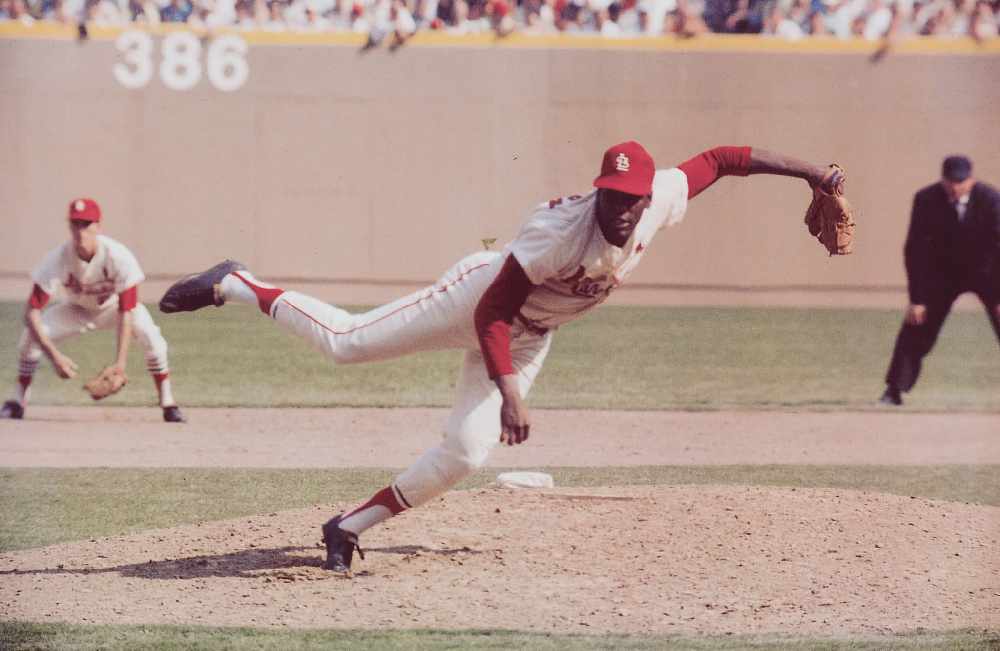

My first sports hero, Bob Gibson, died on Friday.

I came of age in St.Louis, Missouri, a baseball-mad city, home of my beloved Cardinals.

One of my first vivid sports memories was from the summer of 1971. I was splashing around in a hotel pool in Sarasota FL while on family vacation. My father leaned down to the edge of the pool and told me that Gibson had thrown a no hitter the previous day - the only of his brilliant career. My Dad patiently explained to me what a no-hitter meant. From that point forward, Gibson was my favorite player. I was six years old.

Gibson was 35 years old. He was still an elite pitcher, but no longer as dominant as he had been in the 1960s. So, I never saw him in his prime. Still, I quickly learned that Gibby had been the Redbirds' premier superstar in the 1960s when he led the franchise to three World Series and two championships.

The next spring, I ordered Gibson's exceptional autobiography From Ghetto to Glory, through my school's scholastic book program. It was the first "adult" book I ever read. It was my constant companion during the '72 season, Gibson's final brilliant campaign. That little paperback changed my life.

From Ghetto to Glory, as I remember it (I still own that well-read copy, but it's on my mother's book shelf back home, so I can't refer to it today), doesn't include much in the way of overt political proclamations - but it also doesn't shy away from representing the devastating human impact of American structural racism. The book tells the story of Gibson's life. His childhood in Omaha Nebraska. His health struggles as a child. His families struggles. And along the way, the painful ways that young Bob learned he was living in a racist, unjust society.

For me, six and then seven years old in the summer of 1972, these tales of socially systemic cruelty and how they were inflicted on the person who was my hero - how he learned, while still a child, about society's devastatingly painful cruelty towards all black people - his story seared into my soul the abject and utterly disgusting nature of American racism. I understood from that point forward, for the rest of my life, that the society I was living in was actively engaged in a crime against humanity.

Bob Gibson was not a political militant like Muhammad Ali; nor was he an outspoken civil rights advocate like Jim Brown or Lew Alcindor (soon to be known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar). However, Gibson didn't distance himself from the movement - nor did he temper his behavior in any way to make himself acceptable to white America. That strikes me as significant because if there is one thing that everyone acknowledges about Bob Gibson at the height of his glory was that he was Fierce (with a capital F) - as confrontational and competitive as any superstar in the history of American sports.

I was still in my infancy when Bob Gibson thoroughly dominated three World Series in a stretch of five years - right through the middle 1960s - the last period in which the World Series remained unquestionably the premier sports spectacle in the United States. All three of the Cardinals World Series appearances in the sixties went to seven games and Gibson started three times in each - winning the decisive game 7 in 1964 and 1967, over the Yankees and Red Sox, respectively.

I can only imagine how much political resonance Gibson's dominating World Series performances had at that time; spanning the peak years of the Civil Rights Movement to the rise of Black Power. There is no role in American sports, there's no other position - not a quarterback, not a basketball superstar - who can dominate a game like an ace pitcher, who can completely control the narrative from the mound - and no one ever commanded center stage with more authority than Bob Gibson.

Still, even after winning two World Series Game sevens, it is Gibson's performance in Game one of the '68 series that is most often cited as his greatest. The other starting pitcher that day was Denny Mclean, who won 31 games for the Tigers in 1968 (the last time a Major League pitcher won over 30 games). Gibson's 1968 season had been no less impressive. He registered the lowest runs allowed per inning pitched (which is understood as the most important overall statistic for a pitcher) for any pitcher in the history of the modern major leagues. In other words, game one of the 1968 World Series was the most anticipated showdown between two ace pitchers, perhaps in all of major league baseball history. Gibson responded with what is largely acknowledged as the one of the two greatest pitching performances in World Series history (along with Don Larsen's perfect game in 1956). Gibson shut out the Tigers and registered a record-shattering 17 strike outs.

Eight days later, however, a game was played that haunted my childhood even though I didn't watch it at the time (I was still too young) - such was my love for the Cardinals and their great hurler. Gibson had won Game four to give the Cardinals a seemingly insurmountable three games to one lead. However, the Tigers overcame a three run deficit to win Game Five, and crushed the Cardinals in Game Six to even the series - but Gibson was scheduled to take the hill in Game Seven in St Louis. Gibson was riding a record shattering seven game World Series winning streak, going back to 1967 - and the Cardinals were aiming to become the first franchise other than the New York Yankees to win back-to- back World Series titles since 1930.

October 10, 1968 was poised to be the day of Gibson's and the Cardinals' crowning achievement. Instead, it taught me another painful life lesson.

Gibson shut down the Tigers through six innings, but so did the Tigers second ace, Mickey Lolich. Then, in the top of the seventh, Gibson retired the first two batters before a pair of singles put runners on first and second. What followed was what many people feel was the single most influential play in the history of American sports - at least, as it pertained to the business of American sports. The Tigers Jim Northrup hit a deep fly ball to center field, and the Cardinals great center fielder Curt Flood - who usually caught anything within his vast range - mis-judged the ball, allowing the two runners to score. The Tigers went on to win the game and Flood was largely blamed for the loss.

When Cardinal ownership offered Flood less money than he expected in the offseason, many analysts at the time attributed it to Flood's mistake in the 7th inning of game seven (though racism certainly played a significant role too). Flood took issue with the insulting offer - one thing led to another and within a year Curt Flood became the first player in major league sports to challenge the contract rules that had been in place since the inception of professional team sports in America. Flood's rebellion launched the era of free agency and transformed American sports forever.

A few years later, a die-hard seven year old Cardinal fan learned a few more tough life lessons - about loss, and about the savage priorities of American business - as Flood's contract dispute precipitated the break-up of a dynastic team before its time, leaving me a fan of a mediocre hometown team.

Through it all, Bob Gibson remained for me what he represented then - a brilliant man, an unrivalled performer, and one of my many Virgil-like guides through the rings of contemporary America's hell.

Yet nothing could ever diminish the grace, power, intensity, and beauty of Gibby on the mound. Dominating the world, which was his stage - and that for me was also a lesson of transcendence and victory, the fruits of hard-work and perseverance - and that remains as uplifting for me now as it will for eternity.